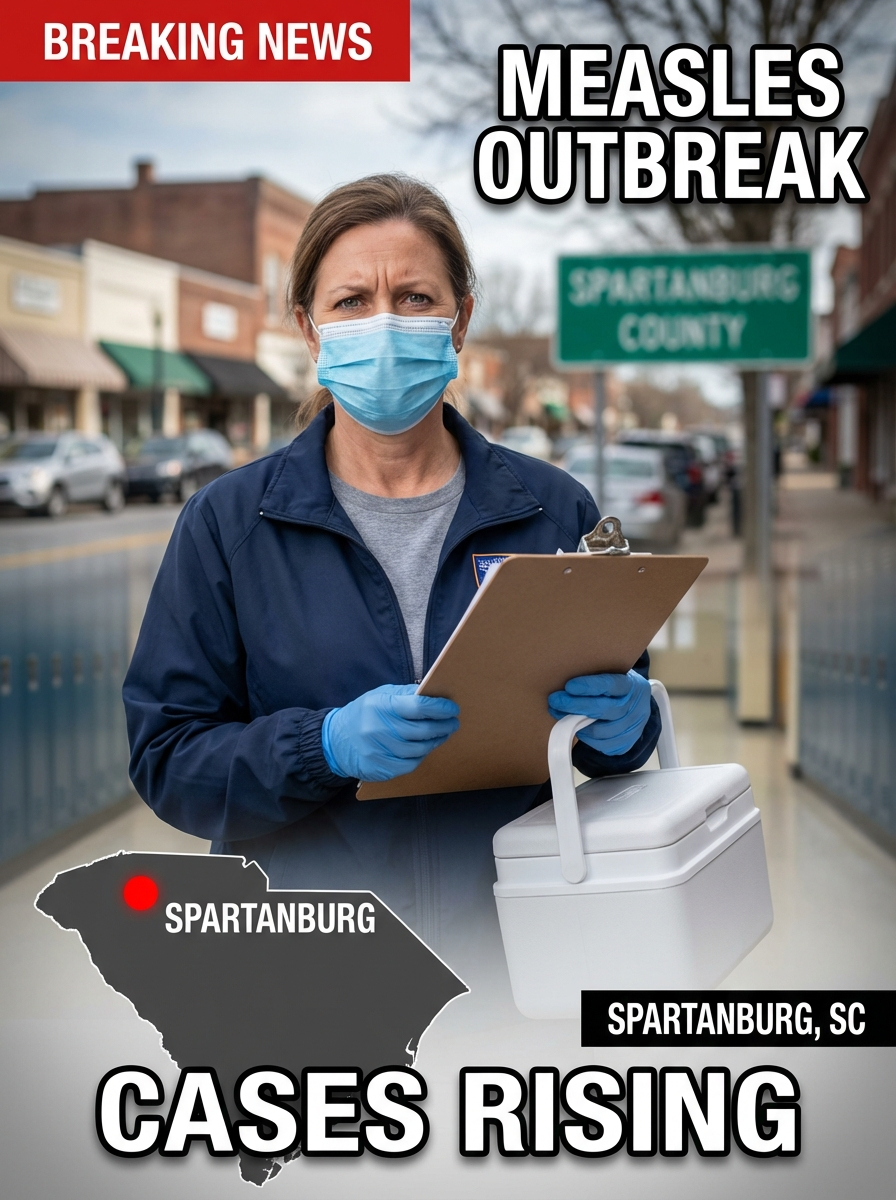

The Mystery Outbreak: What’s Happening in Spartanburg?

SPARTANBURG, S.C. — Fear moves fast. Viruses move faster.

In Spartanburg County, South Carolina, a measles outbreak that began last fall has exploded into one of the largest U.S. surges in decades—turning a disease many Americans associate with history books into a daily, local reality. State health officials say the outbreak is centered around Spartanburg County and has grown to 973 confirmed cases as of Feb. 20, 2026, with new infections still being reported even as the pace appears to be slowing.

Measles is not “mysterious” in the medical sense—its symptoms, spread, and prevention are well understood. What’s shocking is how quickly it can rip through a community once immunity gaps open. The South Carolina Department of Public Health has repeatedly stressed that measles spreads easily through the air, and the number of public exposure sites indicates the virus is circulating beyond just household clusters—raising the risk for anyone not protected by vaccination or prior infection.

So how did a nearly eliminated disease come roaring back?

Public health reporting points to a grim combination: low vaccination coverage, close-contact spread in families and schools, and enough community mixing to turn individual cases into chain reactions. Reuters reports the overwhelming majority of infections in the South Carolina outbreak are in people who are unvaccinated, a pattern consistent with what epidemiologists warn happens when MMR uptake dips below the level needed to prevent outbreaks.

Nationally, measles is surging too. The CDC reported 982 confirmed measles cases in the U.S. in 2026 as of Feb. 19, with most cases linked to outbreaks—meaning Spartanburg isn’t a freak anomaly; it’s a flashing red signal in a larger national picture.

And the internet’s obsession with “Patient Zero”? Health officials typically avoid naming or spotlighting an alleged first case for a reason: measles contact tracing is about breaking transmission, not assigning blame. Identifying the earliest known case is often difficult, especially when early infections can be mild, missed, or misdiagnosed—and privacy laws prevent public disclosure of personal details. Meanwhile, the more urgent question is not “who started it,” but “who is vulnerable next.”

What should residents watch for? Classic measles symptoms include high fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes, followed by a rash. The virus is so contagious that it can linger in the air for up to two hours after an infected person leaves a room—one reason public exposure locations matter so much.

Is this isolated, or a warning of something bigger? Public health experts increasingly treat it as a warning. If one county can become an epicenter, others can too—especially where vaccination rates are low and misinformation spreads faster than immunization appointments. Spartanburg is now a case study in what happens when a preventable virus finds the smallest crack—and kicks the door open.