The 5,000-Year-Old Superbug: Frozen Bacteria Defies Modern Medicine

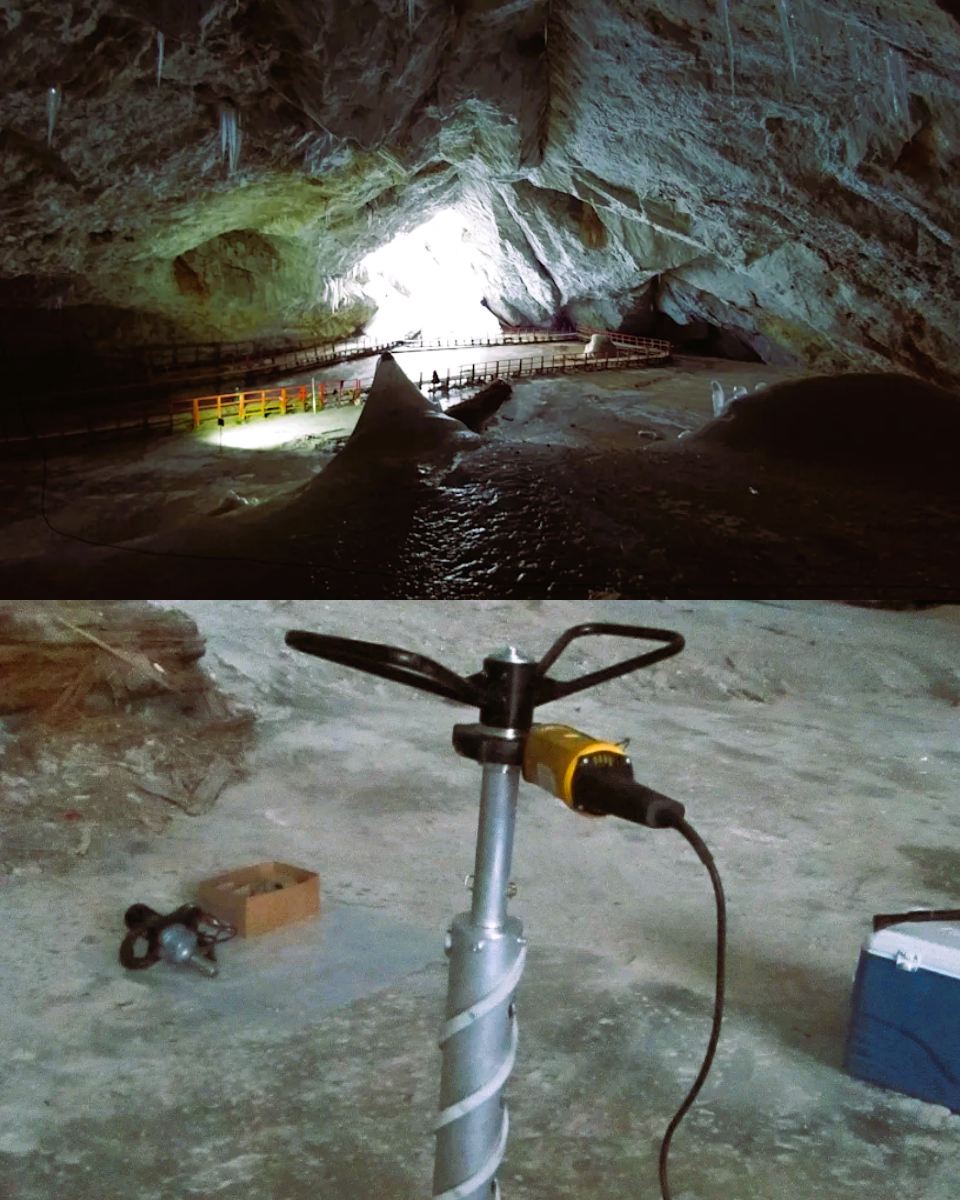

BUCHAREST — A team of Romanian researchers has uncovered an unsettling reminder that antibiotic resistance didn’t begin with modern hospitals or overprescribing—it may have been evolving quietly for millennia. In a new study, scientists reported isolating a bacterial strain sealed within ~5,000-year-old ice from Scărișoara Ice Cave, one of Europe’s largest underground ice caves. The bacterium, Psychrobacter SC65A.3, showed resistance to 10 modern antibiotics, raising new questions about what ancient microbes can carry—and what a warming world might set free.

The discovery is often described online as “permafrost bacteria,” but the study’s setting is more specific—and arguably more eerie: an underground cave ice deposit. Researchers drilled a 25-meter ice core from the cave’s Great Hall, representing an ice archive spanning roughly 13,000 years. Working to avoid contamination, they transported samples frozen and isolated multiple strains in the lab, then sequenced genomes to map survival traits and resistance potential.

When the team tested Psychrobacter SC65A.3 against 28 antibiotics from 10 classes, they found resistance to ten drugs commonly used—or reserved—for serious infections, including rifampicin, vancomycin, and ciprofloxacin, among others. Genomic analysis also identified over 100 resistance-associated genes, suggesting the organism carries a deep toolkit for surviving chemical threats in its environment.

The headline fear is obvious: if ancient microbes with robust resistance profiles are released into modern ecosystems, they could contribute to the wider antimicrobial resistance crisis—especially if resistance genes can transfer to other bacteria. The study’s senior author explicitly warned that melting ice could potentially release microbes and their genes, adding to the global challenge of antibiotic resistance.

But the story is not purely apocalyptic. In a twist that complicates the “superbug” narrative, the researchers also reported that SC65A.3 can inhibit the growth of several major antibiotic-resistant pathogens and contains multiple genes that may produce antimicrobial compounds. In other words: the same ancient biology that looks dangerous could also hint at new tools for medicine and biotechnology.

Scientists who study resistance say the broader lesson is that antibiotic resistance is ancient—a natural outcome of microbes competing with each other long before humans manufactured antibiotics. Reviews of “pristine ecosystem” studies have documented resistance genes in environments ranging from permafrost to isolated caves, including resistance elements resembling modern clinical mechanisms.

Could this trigger a new global health crisis? Experts caution that “ancient microbe” headlines can outrun the evidence. A single strain discovered in controlled conditions does not automatically translate into an imminent outbreak. The higher-risk scenario is not a lone bacterium resurfacing like a monster, but a gradual ecological mixing of ancient resistance genes into modern microbial communities as climate change reshapes frozen environments.

For now, the discovery is best understood as a warning and an opportunity: the microbial past is not dead—it’s archived. And as the planet warms, scientists are racing to understand what’s in the vault before the vault opens itself.